Why should you volunteer for Layers of London: a volunteers perspective.

We asked our valuable volunteer Margaret about her experience volunteering on the project so far, why she was interested in the project and what she is working on currently.

We asked our valuable volunteer Margaret about her experience volunteering on the project so far, why she was interested in the project and what she is working on currently.

This week we welcomed our new Public Engagement Officer to the team. Amy will be working with schools, community groups and volunteers to promote the project alongside the Volunteer Co-ordinator who will be starting work on the project shortly.

Amy joins us from a similar role on another Heritage Lottery Fund project, The Kenley Revival Project, which aims to protect and preserve the UK’s best preserved fighter airfield. Amy is a teacher by trade and has a thorough knowledge of a wide range of curricula and has taught in many traditional and non-traditional teaching environments.

Some words from Amy:

I am so excited to be a part of the Layers of London team. It is important for me that heritage is accessible for everyone and this project is a great example of how anyone and everyone can contribute to, engage with and connect with their local heritage. History and heritage has always been a huge passion of mine, if I ever have a spare day I am always in a Museum, watching a new Lucy Worsley documentary or my head is in a Mary Beard book! I love discovering new areas of London and their history and am keen to start exploring and meeting the amazing groups, organisations, schools, volunteers and people that will contribute their knowledge and stories to build up these layers on the website.

I am looking forward to meeting and working with the schools, organisations and volunteers in Barking and Dagenham that have contributed to the project so far and the next steps are to engage with at least 7 other London boroughs by the end of Summer Term 2018. Keep your eyes peeled; we may be coming to a borough near you!

The project will have many interesting and varied volunteer roles and projects within it too and we will need help to reach our goal of engaging all 32 London boroughs to ensure their heritage is represented. We will be recruiting for these roles in the near future but anyone can contribute to the website NOW! I have been reading some amazing contributions already from stories of conscientious objectors in Haringey to where William Blake had his vision of angels in Peckham. As ever, if you are interested in the project and would like to learn more or would like to register your interest in our upcoming regular project newsletter,get in touch at layersoflondon@sas.ac.uk

Each year, at IES Abroad London, I teach a history of London course. My students are first-year undergraduates from Skidmore College, a liberal arts college in Saratoga Springs, New York State. The course is designed so that students learn to appreciate the social, political, economic and environmental influences that have shaped the development of London over two millennia. More than that, a key goal of these courses is to help first-year undergraduates develop the essential skills that they will need for a successful career – both at university and thereafter.

This year, in addition to the usual examination and essay requirements of the course, I asked all of my students to write something for the Institute of Historical Research’s Layers of London project. Why did I do this? First, I wanted them to realise that there are many ways to produce historical research beyond writing essays. That is not to say that being able to express oneself clearly in an essay format is not important – far from it. But it is to say that graduates today enter a competitive job market and learning how to condense one’s research into a concise 300-word piece for a website is a useful transferable skill for any student to develop. For me, their Layers of London pieces did not replace the longer assignments, rather they complemented each other. Moreover, the Layers of London project is one that will grow and it will be used by historians and researchers interested in the history of London. I thought that for American students spending a term in London on a study abroad programme, producing something for this website was a nice way for them to leave their own personal mark on London’s history.

It was easy enough to set up a team which all the students were able to join by clicking on a personalised link. Prior to choosing a topic which interested them, I took the opportunity to speak to each of my students individually. In all of these sessions I thought it was important not to be too prescriptive: I wanted the students to choose something which engaged them, whether that was a building they walked past every day, a person whose life they found interesting, something connected with a hobby or interest of theirs, or perhaps even a person or place from London’s history with whom or which they could identify. I could not have been happier with their efforts. The students seemed very much to enjoy the freedom of being able to choose a topic of particular interest to them, and they approached the task with some gusto. Many of the students travelled considerable distances across London to take photographs for their website entries, and I was particularly impressed by the original research which they conducted, be that reading nineteenth-century Old Bailey Court Records or knocking on the doors of various institutions across London to find out more about their histories from the people within.

What was most pleasing for me as their teacher, however, was the amount which I learned from their efforts. Now when I walk along Primrose Street on the borders of the City of London and Spitalfields, I know that it was the street on which Mary Wollstonecraft was born on 27 April 1759. Now when I swim at Dulwich Baths, I know that in both World Wars the Baths functioned as much more than just a place where people could swim and exercise. Now, too, I know that St Peter’s Italian Church in Holborn was the church which first catered for the Italian immigrants who settled in the Holborn and Clerkenwell areas in the nineteenth century. As someone who teaches and writes on the history of London, it was a rewarding experience. I look forward to learning more next year.

Octavia Hill Cottages, Southwark. Constructed between 1884 and 1887 these cottages were designed to provide comfortable accommodation for the working poor and provide the spaces for community interaction. They were constructed on land given by the social reformer Olivia Hill to the Ecclesiastical Commission, reflecting Hill’s belief that one should “Do noble deeds not dream them.” (Excerpt from a contribution to the Layers of London website by a student at IES Abroad. For the complete entry see: http://alpha.layersoflondon.org/the-map#/pins/827).

By Rose Mitchell, map specialist at The National Archives

There is a concept of life in Britain just before the First World War as the Indian summer of the Victorian world, a golden age when sunny days were as long as the dresses of ladies taking tea at country house parties, and, as Boris Pasternak wrote in The Last Summer, a time when ‘life appeared to pay heed to individuals’. What was life really like then? An original contemporary source held at The National Archives gives details that help to give a truer picture of how people from a wide cross-section of society lived.

The Valuation Office survey made around 100 years ago was a property valuation for tax purposes; it was such a comprehensive survey of land and buildings that it was dubbed a New Domesday. It has a wealth of detail about people and places.

Maps serve as the means of reference to more than 95,000 Field Books which contain descriptions of some nine million individual houses, farms and other properties. The Survey gives us a unique ‘snapshot’ of property and society in Edwardian England and Wales; London case studies are used here, but similar examples may be found elsewhere.

Why and how was the survey carried out?

In the early 20th century much land was still owned by a privileged few, who often got richer as their land increased in value with no effort on their part. This was beginning to be seen by many people as a social injustice. In 1909 the Chancellor of the Exchequer was David Lloyd George (who became Prime Minister in December 1916), after whom the survey is sometimes named. His Liberal Government’s so-called ‘People’s Budget’ introduced a new tax on any increase in land values due to the state rather than to landowners’ own efforts.

First, a valuation was made of all land in the United Kingdom, to fix the base line from which increases in value would be calculated. Each property was given a plot number, unique within its income tax parish, which was written on the relevant map, and a description written in the related Field Book. The amount of detail varies but can give much information about the use and value of lands and buildings, and names of their owners and occupiers.

Original maps

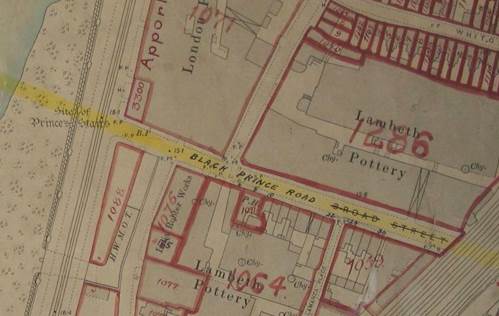

The Survey included all sorts of buildings where people lived, worshipped, were educated and worked. Workplaces range from shops and banks to factories. The Survey used printed Ordnance Survey maps on which plot numbers were written. This map shows the location of the Lambeth and London Potteries, just south of the River Thames, one of the Royal Doulton sites until 1956. ‘Chy’ marks the location of the tall pottery chimneys. Handwritten plot numbers – 1286 and 1064 – link to Field Book entries.

Map showing the Royal Doulton pottery in Lambeth (The National Archives catalogue reference: IR 121/16/4)

Field Books: from gentlemen’s club to slums

Field Book entries state who owned and occupied a property, how much it was worth, and rent paid. There is often a description, perhaps giving the internal layout of a building or stating when it was built, sometimes even with a sketch plan.

The entry for St Stephens Club, the MPs’ club, in its original building on Victoria Embankment, mentions a subway from the basement to the Houses of Parliament, and to the railway station and steamboat pier, should a discreet getaway be needed. A typical gentlemen’s club, it contained dining, drawing and smoking rooms, a library, and rooms for playing cards and billiards.

![[Caption 2] Field book entry for St Stephens Club, Westminster (The National Archives catalogue reference: IR 58/91295)](https://layersoflondon.blogs.sas.ac.uk/files/2016/12/Image-2-St-Stephens-club-TNA-Rose-Mitchell-1-1024x253.jpg)

[caption 2] Field book entry for St Stephens Club, Westminster (The National Archives catalogue reference: IR 58/91295)

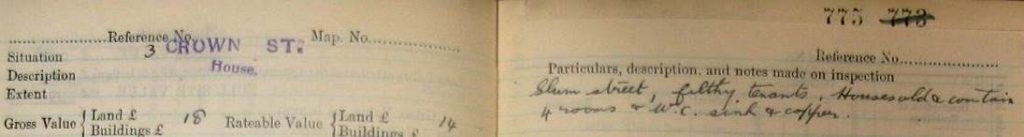

If the survey provides plenty of evidence of how the upper classes lived, there are contrasting descriptions of homes at the other end of the social scale, too, from rural hovels to city slums. Information written in Field Books varies between districts and surveyors, who might write very little when faced with endless rows of houses.

Looking at Charles Booth’s poverty maps of around 1900 showing the poorest areas of London, we find part of Camberwell looked rather black, which meant that Booth found these streets the hangouts of the worst criminal classes. The Field Book entry for 3 Crown Street suggests that the surveyor did not want to spend much time in this area; he simply noted ‘slum street, with filthy tenants’. The 1911 census entry for this property shows the four rooms divided among two families, with 15 people crowded in one small house.

Crown Street in Camberwell appears on Charles Booth’s London poverty map as inhabited by the ‘lowest class’

(courtesy of London School of Economics)

Part of the Field Book entry for 3 Crown Street, Camberwell (The National Archives catalogue reference: IR 58/27892 plot 775)

Insight into the era

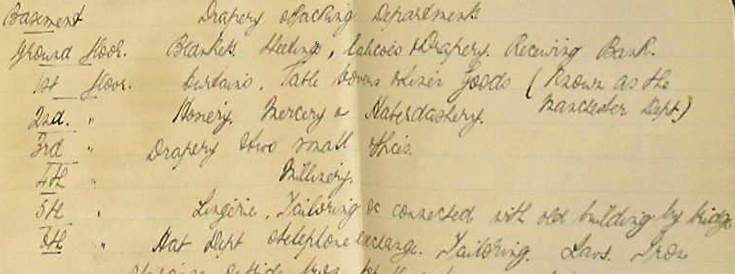

The Field Books give an idea of the extent to which modernity was spread across districts, with mention of electricity, garages for motor cars, music halls and cinemas. A telephone exchange connected the Cooperative Wholesale Stores headquarters in Whitechapel to its branches elsewhere in the country. Unusually the Field Book entry has a picture pasted in, a printed history of the building, and a manuscript list of departments: haberdashery on the second floor, millinery on the fourth, hats up on the sixth floor, and its own instore bank.

Part of the Field Book entry for the Whitechapel Cooperative Wholesale Store (The National Archives catalogue reference: IR 58/84839 plot 5665)

Case study: Jewish East End

This map of part of Spitalfields shows the area of Frying Pan Alley and the Jews’ Free School to the west, with a ‘tenter ground’ handwritten indicating an area for drying cloth.

In Brune Street plot 1006 is revealed by the Field Book entry to be a Jewish soup kitchen which the photograph shows had opened in 1902 – the Jewish date is also given – and only closed in 1992, being refurbished as bijoux flats for City workers.

Part of the Valuation Office map showing Spitalfields (The National Archives catalogue references: map IR 121/20/25; Field Book IR 58/84296 plot 1006; image from Jewish East End website)

The Valuation Office survey records, along with other contemporary sources, can thus throw light on people and places at a particular moment in history.

Please note that Valuation Office Field Books can only be viewed at The National Archives. For more information on the Valuation Office Survey, its history, contents and how to access its information see the research guide Valuation Office survey: land value and ownership 1910-1915.

Posted by Rebecca Read, Layers of London Administrator

One of the rewarding parts of working on the Layers of London project so far has been having the opportunity to visit archives and libraries around London particularly those that may not be so well known.

Arup is the internationally renowned architecture and civil engineering firm responsible for such iconic structures as the Sydney Opera House and, the last project that Ove Arup designed himself, Kingsgate Bridge in Durham. Closer to home, Arup were the civil and structural engineers responsible for building Chamberlin, Powell and Bon’s Barbican Estate in the 1960s and 70s in the City of London.

Arup’s photo library covers the entire history of the firm and Daniel Imade, Senior Photo Librarian, made us welcome in their Fitzroy Street headquarters to talk to us about the collection and show us some of the images of projects across London. Concentrating on our pilot phase in Barking and Dagenham, we found some fascinating civil engineering projects and architects’ photographs of schools and hospitals in the borough.

Borough archives often have collections that deserve a wider audience for what they can tell us about London and the lives of Londoners. When we visited Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives earlier this month we stayed to look at the photographic exhibition, “Brick Lane Born Exhibition: Some photos by Raju Vaidyanathan, 1983-1989”

It is a series of extraordinary images capturing a teenager’s view of life in the East End. Whilst the photographs themselves evoke the huge social and political changes of the 1980s, it was the photographer’s idiosyncratic captions that make the exhibition so compelling. Raju Vaidyanathan is still living in Brick Lane and documents the changes he has seen in a very personal way and vivid way.

The exhibition is on until 7 January.

http://www.ideastore.co.uk/local-history-brick-lane-born

Our aim is that Layers of London can provide a place to bring together these kind of fascinating and disparate collections to build a history of the city that includes everyone.

As Ove Arup is quoted on the company website “…our lives are inextricably mixed up with those of our fellow human beings, and that there can be no real happiness in isolation…” Ove Arup, 1970.

A series of photographs by Saira Awan capture the family lives of residents of the Gascoigne Estate. These were on display in the public space around some of the buildings as part of the Open Estate Festival.

The Open Estate Project is a London mapping project of a different sort- documenting the memories and reflections of residents of a large housing estate in London that is currently being redeveloped to make way for new housing. It is one of the many projects of Studio 3 Arts, a charity set up to develop and deliver socially-engaged, co-created artistic practice in North East London and West Essex.

A fascinating collection of visual material resulted from the project – this includes portraits of families relaxing at home, as well as photos of the Estate during moments of pivotal change – showing residents doing everyday chores with the bulldozers at work in the background, or capturing the effect of the seasons on an urban landscape that will never be there again – like the modernist checkerboard created by the snow-covered paths and buildings.

An exhibition of wide ranging artistic output captured personal reflections on what objects and items people cherished, made out of clay – an old bathtub, a laptop, plates and saucers. To complement that, a cabinet of travelling treasures displayed people’s real mementos: an action man doll, a mantle clock, a pearl necklace.

Open Estate asked local residents to think of what was valuable to them and why. Here are some of the answers.

As one of the panels in the evocative display told a crowd of fascinated visitors:

“As Gascoigne moves through the regeneration process, some objects may be the last remaining elements of a former flat – the valve from a hot water cylinder – a lock and key that used to secure a home. But other objects demonstrate moving forward, a Disney keyring from a family holiday that will hold the key to a new home, and mugs that will be the first out of the removal box for a restorative hot drink.”

One of a collection of goblets created to represent the urban evolution of the Gascoigne Estate, from the property of the aristocratic Gascoigne Family, to Victorian terraces, to the current, rapidly disappearing, blocks of flats.

A ceramicist, Simeon Featherstone, worked with local residents of all ages to produce a collection of glazed ceramic globlets, made of clay dug up from the estate itself, some of these include imprints of Gascoigne’s textures: the coarse fibres of a carpet, and the swirls of wall paper. Among the most fascinating were pieces with maps of the different phases in the life of the estate – like the ones shown here, placing the plan of Victorian terraces below that of the 1950s blocks that replaced them, the very structures that are now being erased. The goblets were a nod to the history of the Gascoigne family, wealthy aristocrats who once owned the land.

The project’s final celebration culminated with a symposium at which heritage specialists, planners, community members and local officials put their heads together and reflected on what had been taking place. One comment from a local resident summed it all up. “I watched a programme on the Tudors which featured a painting showing Henry VIII holding a skull – the skull was a reminder that nothing is permanent; that everything must change. So it must!”

Apart from its obvious benefits in bringing a community together to share and support each other during a period of significant change, a project like Open Estate is of great value to urbanists, and to those historians of the future who can look back at its photos, its drawings and its recordings, and understand first-hand what sort of community this was, in many different ways.

It is exactly the sort of information Layers of London can help preserve.

As Steve Lawes, Trainee Project Manager for the Open Estate Project says “The Layers of London project is a fantastic opportunity for ordinary people to access their history via visual and written records. It will allow multidisciplinary and multimedia archival and personal histories to be easily accessible, easily edited and easily understood.

For Open Estate, which is unearthing the personal and social histories of the Gascoigne Estate in Barking, Layers of London will allow us to unearth stories from people we might not have otherwise met or conversed with, and users will be add their memoirs and photos to certain places, potentially giving us a more detailed, and most of all personal, historical record. The format of adding memories and histories to a map will make people think about space, time and history in a different way to what they might learn from an information sign at a museum, or from a book. “

To find out more about this fascinating project click here.

By Seif El Rashidi, Layers of London Project Development Officer

One of the current activities of the Layers of London project is to explore the local partnerships that can be created to bring together a community of people who can test the Layers website as it develops and then start adding content in the form of images, film- and sound-clips, text and links. These user-led projects will help demonstrate the website’s full potential and encourage others to contribute their own material.

Our initial search in Barking revealed that there is a very strong sense of identity in the borough, which is excellent, as there is nothing like local enthusiasm and interest to lead to the development of successful heritage projects. So far, we have found that all of those we have contacted are interesting in getting involved, or at least supporting the project going ahead.

We also found a pleasingly wide range of institutions that see the Layers of London as being of potential benefit to them. These include:

DABD UK, a Barking-based charity that works with socially-excluded people around the UK, and which has a collection of photos chronicling its first 50 years that it would very much like to digitise and make publically accessible. It also has the volunteers that can do this, some of whom would learn new IT skills in doing so.

Eastbury Manor House, a Grade I 16th century country estate, today surrounded by interwar residential development, which is currently embarking on a project to record oral histories from volunteers who have worked in the house over the past few decades. Layers of London appears to be an ideal place to make these accounts available and accessible to the widest possible audience.

The Catholic Diocese of Brentwood (which includes Barking), which has an excellent archive that includes invaluable accounts of East London during the war. Layers can be used to raise the profile of this well-managed collection and draw attention to valuable unpublished material it contains.

View of the archive of the Catholic Diocese of Brentwood, a valuable source of information about the modern history of Barking and Dagenham.

Another advantage of Layers is that it can serve as a platform that significantly prolongs the lifespan of other heritage projects. For example, Barking’s Studio 3 Arts is leading a project called Open Estate which documents the memories of residents of the Gascoigne Estate – home to around 7000 people and currently subject to demolition and redevelopment. It is the intention that by the end of September, when Open Estate draws to close, material capturing the memories and experiences of Gascoigne residents can be accessibly preserved through the Layers website, perhaps helping to preserve some elements of community identity in virtual form.

Potential projects with Eastside Community Heritage, a leading community heritage organisation, St Margaret’s, the church in the grounds of Barking Abbey, one of the borough’s most important historic sites, and the local archive, are all examples of other local links being pursued.

In parallel, thanks to Historic England’s Heritage Schools Programme, we have established links with a number of local schools that are interested in getting involved in the georeferencing process, either as part of their formal learning programme, or as an extra-curricular activity. To date, these schools include Eastbury Community School, Eastbrook School, Southwood Primary, Riverside, Becontree Primary, James Cambell Primary, All Saints Catholic School, and Gascoigne Primary.

The number of individuals expressing an interest in volunteering, and our links to a wide network of groups outside the borough are increasing.

We eagerly await the completion of the prototype website to take things further forward.