Place and society in Edwardian England: the Valuation Office survey

By Rose Mitchell, map specialist at The National Archives

There is a concept of life in Britain just before the First World War as the Indian summer of the Victorian world, a golden age when sunny days were as long as the dresses of ladies taking tea at country house parties, and, as Boris Pasternak wrote in The Last Summer, a time when ‘life appeared to pay heed to individuals’. What was life really like then? An original contemporary source held at The National Archives gives details that help to give a truer picture of how people from a wide cross-section of society lived.

The Valuation Office survey made around 100 years ago was a property valuation for tax purposes; it was such a comprehensive survey of land and buildings that it was dubbed a New Domesday. It has a wealth of detail about people and places.

Maps serve as the means of reference to more than 95,000 Field Books which contain descriptions of some nine million individual houses, farms and other properties. The Survey gives us a unique ‘snapshot’ of property and society in Edwardian England and Wales; London case studies are used here, but similar examples may be found elsewhere.

Why and how was the survey carried out?

In the early 20th century much land was still owned by a privileged few, who often got richer as their land increased in value with no effort on their part. This was beginning to be seen by many people as a social injustice. In 1909 the Chancellor of the Exchequer was David Lloyd George (who became Prime Minister in December 1916), after whom the survey is sometimes named. His Liberal Government’s so-called ‘People’s Budget’ introduced a new tax on any increase in land values due to the state rather than to landowners’ own efforts.

First, a valuation was made of all land in the United Kingdom, to fix the base line from which increases in value would be calculated. Each property was given a plot number, unique within its income tax parish, which was written on the relevant map, and a description written in the related Field Book. The amount of detail varies but can give much information about the use and value of lands and buildings, and names of their owners and occupiers.

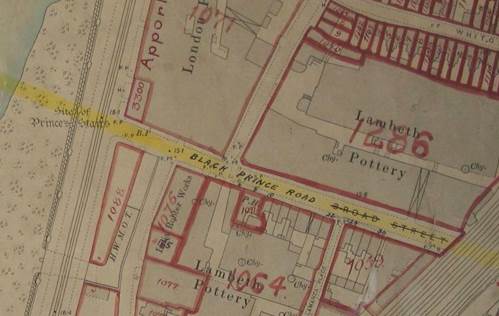

Original maps

The Survey included all sorts of buildings where people lived, worshipped, were educated and worked. Workplaces range from shops and banks to factories. The Survey used printed Ordnance Survey maps on which plot numbers were written. This map shows the location of the Lambeth and London Potteries, just south of the River Thames, one of the Royal Doulton sites until 1956. ‘Chy’ marks the location of the tall pottery chimneys. Handwritten plot numbers – 1286 and 1064 – link to Field Book entries.

Map showing the Royal Doulton pottery in Lambeth (The National Archives catalogue reference: IR 121/16/4)

Field Books: from gentlemen’s club to slums

Field Book entries state who owned and occupied a property, how much it was worth, and rent paid. There is often a description, perhaps giving the internal layout of a building or stating when it was built, sometimes even with a sketch plan.

The entry for St Stephens Club, the MPs’ club, in its original building on Victoria Embankment, mentions a subway from the basement to the Houses of Parliament, and to the railway station and steamboat pier, should a discreet getaway be needed. A typical gentlemen’s club, it contained dining, drawing and smoking rooms, a library, and rooms for playing cards and billiards.

![[Caption 2] Field book entry for St Stephens Club, Westminster (The National Archives catalogue reference: IR 58/91295)](https://layersoflondon.blogs.sas.ac.uk/files/2016/12/Image-2-St-Stephens-club-TNA-Rose-Mitchell-1-1024x253.jpg)

[caption 2] Field book entry for St Stephens Club, Westminster (The National Archives catalogue reference: IR 58/91295)

If the survey provides plenty of evidence of how the upper classes lived, there are contrasting descriptions of homes at the other end of the social scale, too, from rural hovels to city slums. Information written in Field Books varies between districts and surveyors, who might write very little when faced with endless rows of houses.

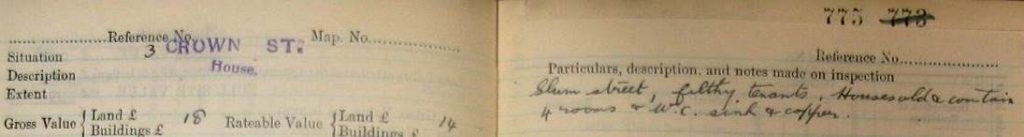

Looking at Charles Booth’s poverty maps of around 1900 showing the poorest areas of London, we find part of Camberwell looked rather black, which meant that Booth found these streets the hangouts of the worst criminal classes. The Field Book entry for 3 Crown Street suggests that the surveyor did not want to spend much time in this area; he simply noted ‘slum street, with filthy tenants’. The 1911 census entry for this property shows the four rooms divided among two families, with 15 people crowded in one small house.

Crown Street in Camberwell appears on Charles Booth’s London poverty map as inhabited by the ‘lowest class’

(courtesy of London School of Economics)

Part of the Field Book entry for 3 Crown Street, Camberwell (The National Archives catalogue reference: IR 58/27892 plot 775)

Insight into the era

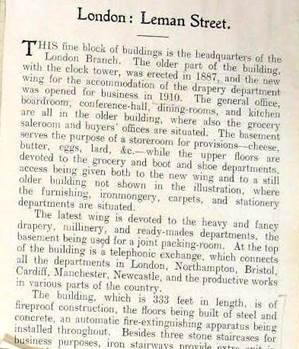

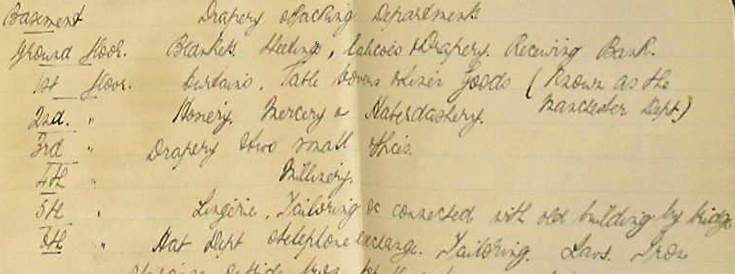

The Field Books give an idea of the extent to which modernity was spread across districts, with mention of electricity, garages for motor cars, music halls and cinemas. A telephone exchange connected the Cooperative Wholesale Stores headquarters in Whitechapel to its branches elsewhere in the country. Unusually the Field Book entry has a picture pasted in, a printed history of the building, and a manuscript list of departments: haberdashery on the second floor, millinery on the fourth, hats up on the sixth floor, and its own instore bank.

Part of the Field Book entry for the Whitechapel Cooperative Wholesale Store (The National Archives catalogue reference: IR 58/84839 plot 5665)

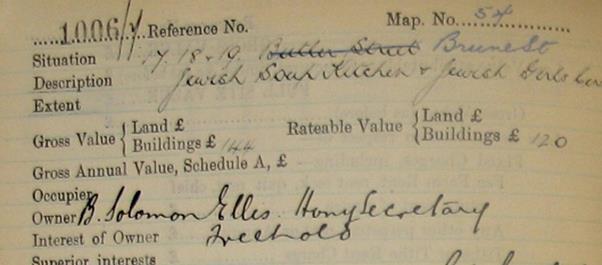

Case study: Jewish East End

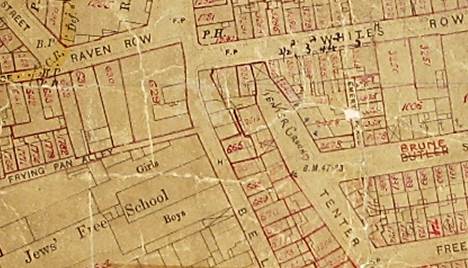

This map of part of Spitalfields shows the area of Frying Pan Alley and the Jews’ Free School to the west, with a ‘tenter ground’ handwritten indicating an area for drying cloth.

In Brune Street plot 1006 is revealed by the Field Book entry to be a Jewish soup kitchen which the photograph shows had opened in 1902 – the Jewish date is also given – and only closed in 1992, being refurbished as bijoux flats for City workers.

Part of the Valuation Office map showing Spitalfields (The National Archives catalogue references: map IR 121/20/25; Field Book IR 58/84296 plot 1006; image from Jewish East End website)

The Valuation Office survey records, along with other contemporary sources, can thus throw light on people and places at a particular moment in history.

Please note that Valuation Office Field Books can only be viewed at The National Archives. For more information on the Valuation Office Survey, its history, contents and how to access its information see the research guide Valuation Office survey: land value and ownership 1910-1915.